The Shot Of A Lifetime

The Shot Of A Lifetime

It was the shot of a lifetime. Certainly Ray Lussier’s lifetime.

It was the shot of a lifetime. Certainly Ray Lussier’s lifetime.

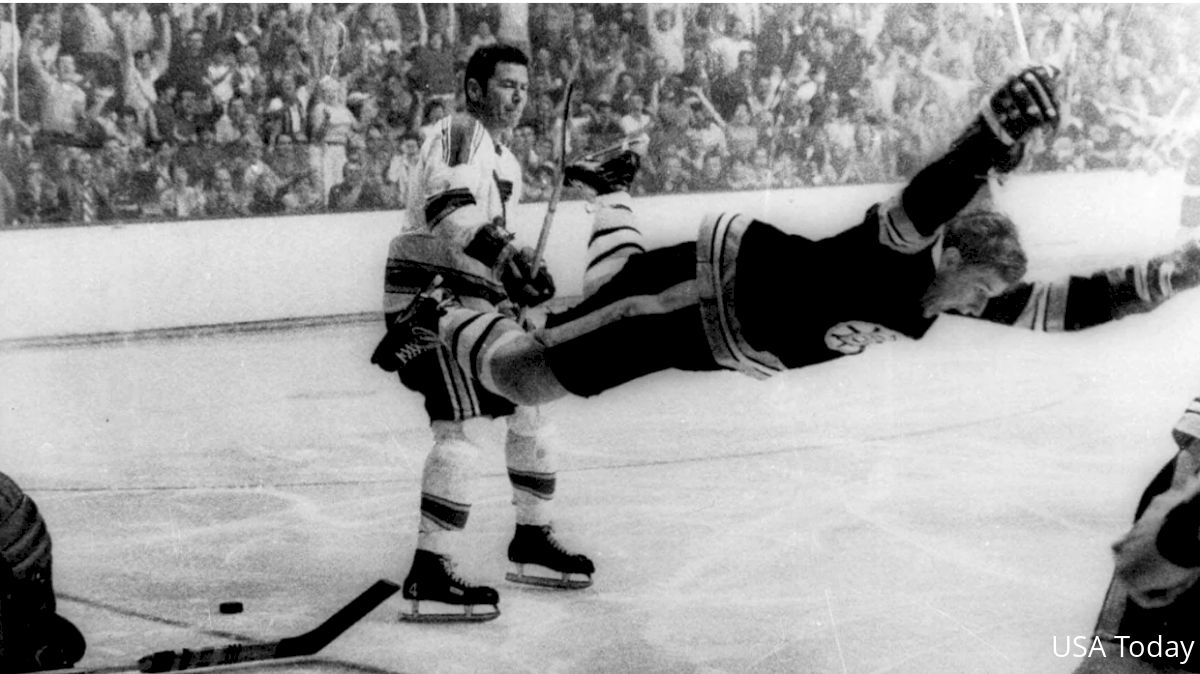

On May 12, 1970, two days after snapping Bobby Orr’s Stanley Cup-Winning goal, his paper the Record American captioned his photo thusly: “This photo is, without a doubt, the greatest action hockey picture of all time.” And Lussier’s masterpiece has withstood the test of time, remaining exactly what the Record proclaimed it to be, “the greatest.”

Ray bagged his shot with the latest technology, a 35 mm Nikon F with a new gizmo—a motor drive—firing away from his rival’s camera position. It was a full combination of tech, luck and old-fashioned street hustle that allowed Lussier to reach the zenith of sports photo journalism. Yes, there was good fortune in that Bobby Orr came flying towards Ray’s lens, but minutes earlier, Ray gambled by lugging his gear 250’ to the Bruins attacking end, prior to immortalizing Orr’s moment. Here’s how it all went down over 49 years ago.

Mother’s Day, May 10, 1970. The Bruins and their fans were looking to sweep the nascent St. Louis Blues in the Finals, and clinch their first Cup in 29 years. Ninety degree temps in Boston had turned the old Garden into a sauna; sweat flowed alongside the beer at the ancient barn with no air conditioning. The Record’s veteran shooter Lussier had his official camera position at the east end of the Garden, near the Zamboni entrance, the end of the rink that the Bruins attacked twice a game. But when St. Louis forced the game into overtime, he would be shooting Blues on the attack for the next 20 minutes. Lussier was compelled to think on his feet.

Ray knew that if St. Louis scored in overtime, it wouldn’t really mean anything,” said his former colleague Stan Forman, speaking to the web site Deadspin. “But if the Bruins scored, they’d win the Cup. Ray was smart enough to put himself in the right place.”

That place was in the west end, in the seat of a photographer from Record rival Boston Globe. According to legend, the Globe shooter was in a crowded beer line, looking to slake his thirst along with 13,909 other fans. That gave Lussier the opening he needed.

“I’m not surprised,” said Ray’s son Randy in an interview with ESPN. “He just took a seat and put his lens in the little cutout in the glass, and overtime began.”

It took Orr and the Bruins all of forty seconds to eliminate the Blues, and start a hockey party for the ages. Lussier was the only one to hear his new-fangled motor dive whirring. As the Garden transitioned to pure bedlam, Ray found himself face-to-face with his competitor from the Globe.

“What are you doing in my stool?”

“Oh, you can have it back,” said Lussier. “I got what I need.”

As the Garden rocked, Ray slid out and hustled over to the Record American offices. He actually did not know what he had in his analog camera, until the negatives came out of the darkroom’s chemical bath.

Lussier grabbed Forman who had just come from the game himself, and revealed the strip of three negatives from the sequence. “It was just fantastic,” said Forman, who then described the deluge of calls after Lussier’s photo was published in a two page spread. “How do I get copies? I want more papers! They couldn’t have printed enough papers.”

Orr’s moment in time, perfectly framed in a state of sheer exultation, was the driving force behind the NHL’s Play of the Century in 2000, and the bronze statue erected outside the new Boston Garden in 2010. According to the Lussier family, Ray’s greatest reward was getting invited to the Bruins reunion in 1990, and posing with the legendary Orr. One year later, at age 59, Lussier died of a heart attack. His legacy, however, remains in bronze, print and posters throughout New England, the greatest hockey photo of all time.